Nothing lasts forever; great boulders are ground to sand by waves, mighty mountains are washed into the sea, and your rim brakes slowly eat away at your sidewalls until you get nervous enough to do something about it.

I recently replaced both of my rims (DT Swiss TK540 touring rims) after three and a half years of hard abuse, so I had an opportunity to compare the old worn-out rims to the new ones and answer a scientific question: just how much stiffness do your rims lose when you wear them down past the wear indicator marks? And does that loss of stiffness matter for the structural stability of your wheels?

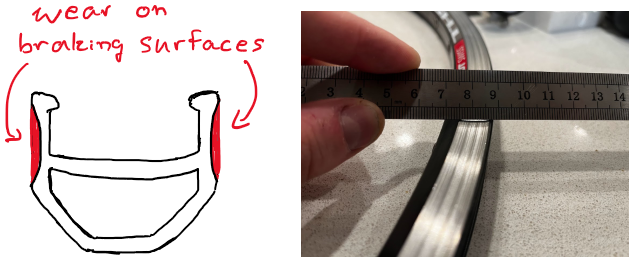

These rims have wear indicators, which are little dimples with a specific depth. Once the sidewalls wear down to the same depth as the dimple, the mark disappears. As you can see below, the rims have been worn down past the depth of the wear indicator (which is probably pretty conservative). I ordered new rims, and after a very long pandemic-shortage wait, I rebuilt my wheels, re-using the old hubs and spokes.

What is rim stiffness?

The stiffness of a rim (or stiffnesses; there are three important ones) is a measure of its resistance to changing its shape under load. Note: stiffness is different from strength, which is a measure of how much load the rim can withstand without suffering some kind of permanent damage. Stiffness is the constant of proportionality between the recoverable (elastic) deformation and the applied load.

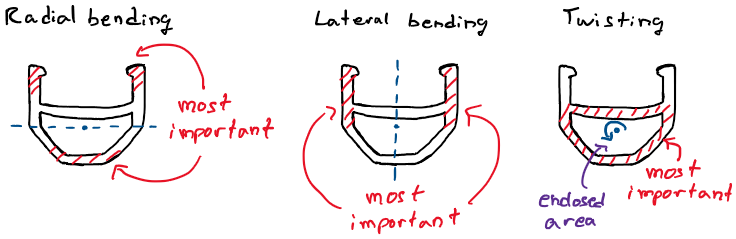

The three most important deformation modes of the rim are radial bending, lateral bending, and twisting; and there is a stiffness associated with each mode. The rim has other modes, like stretching along its axis and shearing, but these modes are so insignificant compared to the bending and twisting modes that their associated stiffness might as well be infinite.

Radial bending

Lateral bending

Twisting

The rim has other deformation modes that involve distorting its cross-section–for example, the tension in the tire sidewalls pull laterally on the tire beads and cause the rim sidewalls to bow away from each other–but I’m going to ignore those here too.

Should I care about rim stiffness?

The rim and spoke work together to support the weight of the bike, and the total stiffness is a complicated function of both. But a stiffer rim will make a stiffer wheel, all else being equal. Wheel stiffness is probably not all that important per se. But tacoing a wheel is actually a form of buckling failure, which is essentially a failure of stiffness. So the wheel stiffness is somewhat important insofar as it pertains to wheel strength.

The rim stiffness also plays a role in how much spoke tension the wheel can safely support without buckling. For most double-wall rims, the buckling tension is so high that you should worry about the nipple fracturing or pulling through the rim before you worry about buckling, but for a single-wall or very slender rim, you can reasonably reach this maximum tension while building a wheel. You'll notice the wheel start to suddenly go out of true in two lateral waves as you approach the maximum safe tension, and you'll know it's time to back off. So it’s conceivable that you could build a wheel with a safe tension, but then as the rim wears out the safe tension decreases until your wheel starts to taco just from the spoke tension.

What makes a rim stiff?

The rim stiffnesses above are determined by the material and the shape of the cross-section only. For bending, the material furthest away from the geometric center (centroid) of the cross-section contributes the most to the bending stiffness. This is why I-beams are shaped the way they are; the two flanges are spaced far apart to maximize the bending stiffness in one direction.

For twisting stiffness, the situation is much more complicated. But roughly speaking, closed contours like the hollow section of a double-wall rim contribute the most to the twisting stiffness. The stiffness contributed by the contour depends on the enclosed area inside the contour, and the wall thickness and perimeter of the contour. For open contours, like a single-wall rim or the sidewalls of any rim, the contribution to the twisting stiffness depends on the wall thickness and total perimeter of the contour. Generally, the twisting stiffness of closed contours is much greater than the twisting stiffness of open contours. You can discover this yourself by trying to twist a paper towel tube, and then cutting a slit along its entire length and twisting it again.

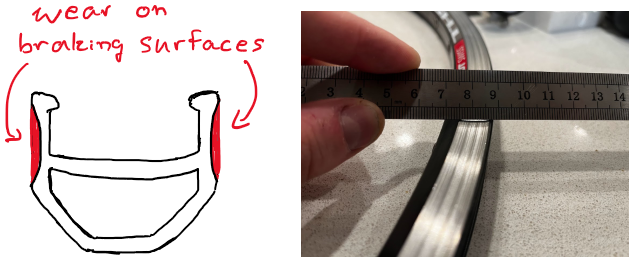

Your brakes eat away at the sidewalls over time, leaving a concave impression. Comparing the wear pattern with the diagrams above, we expect the lateral bending stiffness to be most affected by rim wear, followed by twisting stiffness and radial bending stiffness.

Acoustic stiffness test

I measured the rim stiffness using the acoustic technique I developed with Patrick Peng and Oluwaseyi Balogun. The gist of the experiment will be familiar to anyone who took some physics in high school or college: a system with stiffness and mass has a natural resonant frequency that depends on the square root of the ratio of the stiffness to the mass. This law applies equally to a kid bouncing on the end of a diving board, a vibrating tuning fork, and a bicycle rim. Hang the rim by a piece of string through the valve hole and strike it with a mallet of some kind and it rings at a set of discrete frequencies called modes. By striking it on its inside edge or on its sidewall, you can ring the radial bending modes or its lateral and torsional modes. From the frequencies of the first few modes, along with a measurement of its mass and radius, you can calculate all three stiffnesses.

We compared the acoustic measurement with more direct measurements of the stiffness obtained by applying forces to the rim and measuring its deflection. The accuracy depends on the rim shape, but is generally very good; within 10% compared with the direct method. But for a given rim shape, the precision and repeatability of the acoustic technique is much better than that: probably within 1% or so.

Results

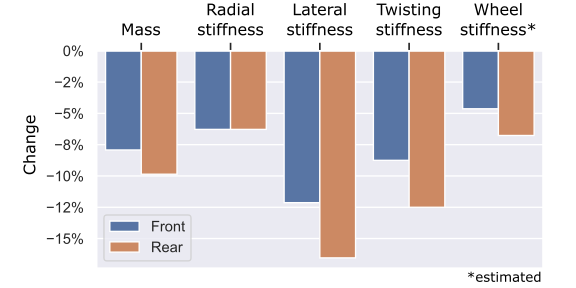

Both rims were worn well beyond their wear indicator marks. The extent of the damage is apparent both in the concavity of the sidewalls and in the loss of mass: the front and rear rims lost about 8% and 10% of their mass, respectively. The stiffnesses were not all equally affected: both rims only lost about 6% of their radial stiffness. They lost about 9% and 12% of their twisting stiffness. The lateral stiffness was the most affected: the front rim lost 12% while the rear rim lost more than 16%.

| Rim | Mass (g) | Radial stiffness | Lateral stiffness | Twisting stiffness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New | 568 | 223 | 272 | 80 |

| Worn (front) | 523 | 209 | 239 | 73 |

| Worn (rear) | 512 | 209 | 227 | 70 |

This pattern makes sense if you look at where material is removed. Your brakes eat away at the sidewalls over time, leaving a concave impression. Comparing the wear pattern with the diagrams above, we can see that the loss of material is right in the area which contributes most to the lateral stiffness. The twisting stiffness is somewhat less affected because the top and bottom of the hollow channel are still quite thick. The radial stiffness is barely affected because the sidewalls aren’t as important as the material at the bottom and top of the rim.

The loss of rim stiffness would decrease the stiffness of the wheel as well, but since the spokes (presumably) haven’t lost any material, the change in wheel stiffness should be smaller than the change in rim stiffness. I estimated the lateral stiffness of both wheels using the Bike Wheel Calculator (I didn’t actually measure the wheel stiffness with either rims).

Double-wall vs. single-wall rims

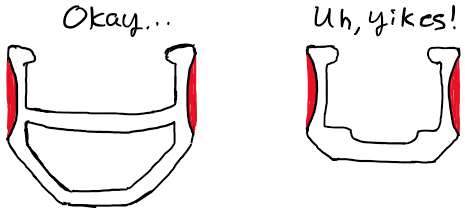

Even a 16% loss of lateral bending stiffness for a 10% loss of mass might not be all that bad, especially for a double-wall rim. I’ve talked to people who didn’t even know there was a problem with their rims until the sidewalls started to crack. So the loss of stiffness is not the first problem you’re going to run into.

But the situation might be quite different for single-wall rims. A single-wall rim is like a C-channel (or like an I-beam with its web attached to one edge of the flanges), and it relies much more heavily on its sidewalls for structural stability. The loss of stiffness from sidewall wear could compromise the already low twisting stiffness and increase the risk of tacoing under load. I would be interested to see what the graph above would look like for single-wall rims and compare the danger of taco failure against the danger of sidewall cracking.

I’m also interested in knowing how manufacturers decide how deep to make their wear indicator marks. Is it actually based on analysis of a particular failure mode, or is there some arbitrary agreed-upon standard for acceptable depth? Or is it a carefully-managed scam to make us buy more aluminum rims?