We ask a lot of our spokes: they support our weight, keep our rims round, and sometimes hold baseball cards or other useful things. They don't ask for much in return other than a good, sturdy rim to keep them from losing tension and the occasional adjustment if your wheel gets damaged. Choosing the right spokes for your wheel will ensure many happy years of riding. When it comes to spokes, there are far fewer choices to make than for your rim. Arguably the most important decision you will make is whether to use butted spokes or straight-gauge spokes.

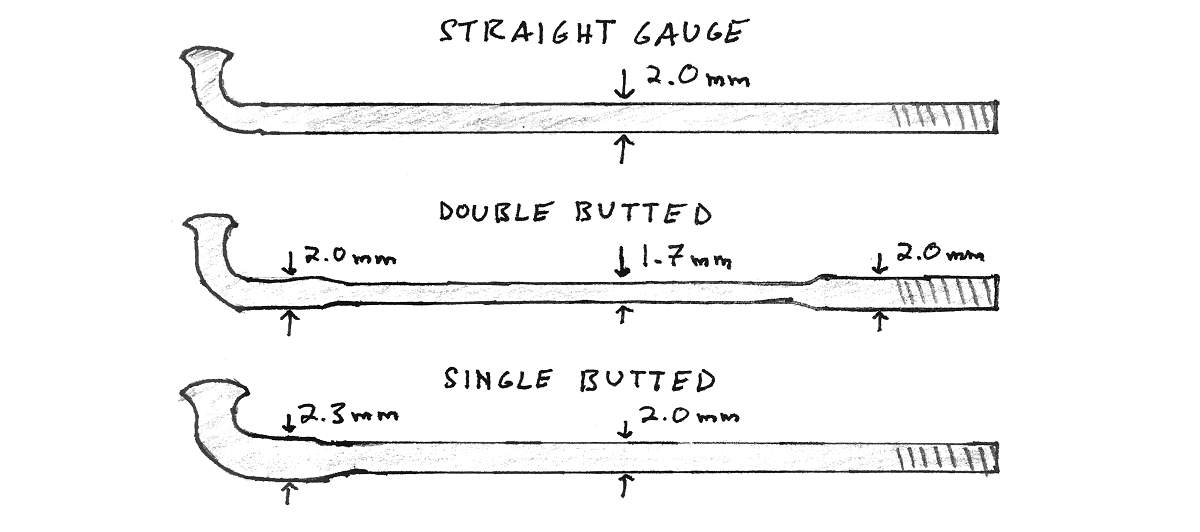

Straight-gauge (SG) spokes have a constant diameter along their entire length from elbow to thread. Butted spokes have at least two distinct diameters: single-butted (SB) spokes are larger at the elbow and smaller along the rest of their length, while double-butted (DB) spokes are larger at the elbow and the thread and smaller in the middle section. They require an additional forming step and are usually around 1.5 to 2 times the cost of comparable SG spokes. (Less common triple-butted spokes resemble double-butted spokes, but are even thicker at the elbow). Ask wheelbuilders why they prefer butted spokes and they will generally cite two things: (1) butted spokes are lighter and (2) butted spokes are "more elastic" and less likely to break due to fatigue.

Let's take a quantitative look at these claims using the Bicycle Wheel App. Starting with the default wheel properties, let's make one wheel with SG 2.0 mm spokes and another wheel with DB 2.0/1.7/2.0 spokes (2.0 mm at the ends and 1.7 mm in the middle). The wheel app doesn't let you specify SG or or DB, so we'll choose the average diameter instead. The effective average diameter for the DB spoke is about 1.78 mm (why?), so we'll round up to 1.8 mm. Set the number of spokes to 32. For simplicity, let's also set the spoke pattern to "Radial." Hit "Calculate" and see what happens! Some of the key properties calculated by the app are given in the table below:

| Rim | Spokes | Radial stiffness | Lateral stiffness | Mass [grams] | Rotating mass [grams] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR18 | SG 2.0 | 4.7 kN/mm | 92.4 N/mm | 767 | 1389 |

| CR18 | DB 2.0/1.7/2.0 | 4.0 kN/mm | 75.5 N/mm | 724 | 1330 |

What exactly does the extra investment in butted spokes buy you?

Less weight

The difference in weight is small but undeniable: the wheel with DB spokes is about 6% lighter. The rotating mass (the mass you "feel" when accelerating) is only about 5% smaller because it's dominated by the rim mass which is the same in both wheels. The app is using an approximation here because it doesn't know exactly how long the thin section is, but it's close enough. Once you factor in the rotating mass of the tire and the nipples the relative weight savings will be even less. Still, many people are willing to pay to shed a few grams.

More flexibility

Oh noes, my stiffnezz! The DB wheel is 14% less radially stiff and 18% less laterally stiff than the SG wheel. Won't it rob me of my precious watts? Probably not. First of all, the radial stiffness is inconsequential because the radial stiffness of the tire is so much smaller. The total vertical stiffness is completely dominated by the tire.

What about the lateral stiffness? The wheel can flex laterally when you are sprinting out of the saddle and rocking the bike sideways. A popular misconception holds that the energy that goes into flexing the bike is somehow lost. This is greatly exaggerated. The stiff materials used in frames return this energy when they spring back. Most riders (and therefore bike manufacturers) try to maximize the stiffness (at least laterally) of their ride. But many people will tell you that butted spokes give a "better ride quality" due to the increased flexibility. So there doesn't even seem to be a consensus on what is desirable here.

Even though the wheel with double-butted spokes is more flexible, it can withstand about the same amount of force before spokes go slack.

Your wheel should be stiff to prevent the wheel from deflection enough to cause spokes to go slack. But the force required to slacken spokes depends on both the stiffness of the wheel and the flexibility of the spokes. The DB wheel will deform more than the SG wheel for the same applied force, but since the spokes are more flexible, the change in tension will be about the same. Take a look at the "Lateral force to buckle spokes" on the "Summary" tab to see details.

Sharing the load

Now for the most-touted benefit of butted spokes: they last longer.

Not every part of the spoke works equally hard. The center section experiences only pure tension and can generally take anything you throw at it. The ends of the spoke have a much tougher job. The elbow is subjected to bending stresses depending on how the head and the J-bend are supported. At the other end, the sharp groove of the threads creates concentrations of stress. For these reasons, the vast majority of spoke breakages happen near the elbow or nipple. Any design change which reduces these stresses will make your spokes last longer.

You will hear some people say that butted spokes "concentrate" the strain in the middle section, thereby taking strain off of the ends. This is not strictly true, or at least it's a little misleading. If you apply the same force to a SG spoke and a DB spoke, the stress, and therefore the strain, will be the same in the ends of each spoke. However, it is true that if you apply the same stretch to the two spokes, the force, and therefore the strain in the ends, will be lower in the DB spoke because it is more flexible overall and requires less force to stretch.

The reason why butted spokes see lower stresses at the ends is because more flexible spokes share load between neighboring spokes more easily. Perhaps you have a "rigid" friend or co-worker who has trouble sharing work or asking for help because they need things to be done their way. Perhaps if they were a little more "flexible," they would have an easier time sharing the load.

Replacing 32 straight gauge spokes with double-butted spokes gives almost the same benefit of 36 straight gauge spokes, but for about 70 grams less.

The extent to which load is shared between neighboring spokes depends on the ratio between the rim stiffness and the spoke stiffness. In engineering terms, this ratio (actually, the 1/4th power of this ratio) is called the "characteristic length." The higher the rim stiffness, the more spokes will share the load. The higher the spoke stiffness, the fewer spokes will share the load.

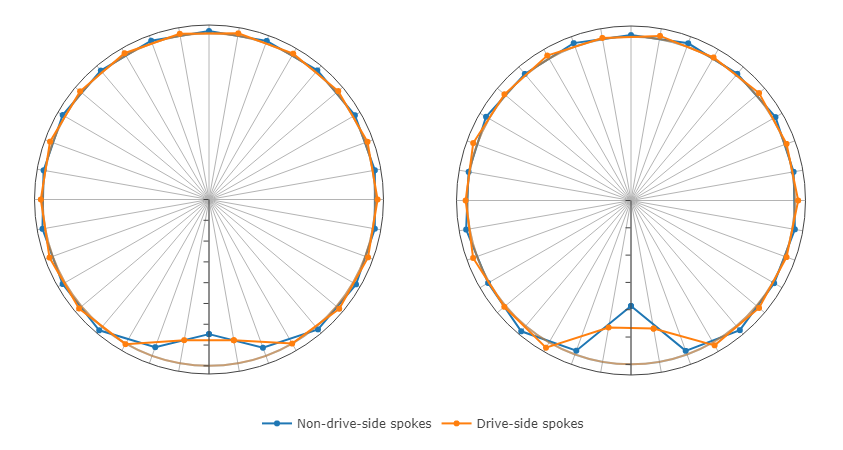

It requires pretty big changes in rim and spoke stiffness to significantly change the load distribution. As an extreme example, the wheels below have the same geometry and number of spokes, but in the left wheel the rim is twice as stiff and the spokes are twice as flexible.

The butted spokes in our example calculation are 19% less stiff than the straight-gauge spokes. Under a 50 kg radial load, the bottom-most spoke sheds 23.82 kg and 22.68 kg in the SG and DB wheel, respectively. This difference (1.14 kg) works out to a 5% reduction in the stress change seen by the spoke. To put this in perspective, going from 32 spokes to 36 spokes reduces the stress seen by a single spoke by about 7%. This reduction in stress, especially for large impacts, increases the fatigue life of the spoke.

That was for radial loads (carrying weight or hitting potholes). For lateral loads the benefit is less than 1% and for tangential loads (like braking or accelerating) the benefit is virtually non-existent. On the other hand, getting the same benefit as a 36-spoke wheel for even less weight can be easily justified if most of the cost of your wheelset is in the rim, hub and labor.

Durability is not strength

On the road, the most common mode of failure is spoke fatigue - the slow build-up of damage resulting from sub-critical loads. A wheel can also fail by rim buckling (generally called "taco-ing") if a large enough force is applied. The strength of the wheel depends on many factors, but the most important factor is the lateral stiffness. A stiffer wheel has a greater ability to maintain its shape and resist buckling.

As seen in the table above, the lateral stiffness of the DB wheel is about 18% lower than the SG wheel. The radial buckling strength is complicated because it also depends on the ability of the spoke to resist buckling, but a rough approximation depending on the spoke stiffness, wheel stiffness, and maximum tension can be derived (see Chapter 5 of my thesis for the details). This model predicts a radial buckling strength of 456 kg for the SG wheel and 403 kg for the DB wheel, a 12% reduction in strength.

If you are building wheels for an extreme application where taco failure is likely, you will want as much lateral stiffness as you can get. In this case, it's probably better to use either straight-gauge spokes, or single-butted spokes with reinforced elbows (2.3/2.0 mm).

Average diameter

The "average diameter" that we put into the simulator is actually the diameter of an equivalent straight gauge spoke which has the same stiffness as the desired butted spoke. In order to determine the effective diameter, we first need to calculate the stiffness of the butted spoke. If the spoke has two distinct diameters, the effective diameter \(d\) is calculated from the following equation:

where \(l_1\) and \(d_1\) are the length and diameter of the thin section, \(l_2\) and \(d_2\) are the length and diameter of the thick section, and \(l\) is the total length. If the spoke has a thick section at both ends, then \(l_2\) is the combined length of those two sections.

References

[1] Matthew Ford, Reinventing the Wheel: Stress Analysis, Stability, and Optimization of the Bicycle Wheel, Ph.D. Thesis, Northwestern University (2018)